The following article appears in the current October/November issue of History Magazine.

Laura Grande looks at different aspects of freak shows in England and the US in the 19th century.

Lazarus and Johannes Baptista Colloredo were one of the world’s most famous siblings. Many cities played host to the brothers as they traveled throughout Europe during the early-17th century. Since their birth in 1617 in Genoa, Italy, the Colloredo brothers both fascinated and horrified the general public.

Lazarus was thought to be quite handsome, appearing otherwise perfectly healthy, but for his conjoined twin brother. Joannes Baptista protruded, upside down, from his brother’s chest. He was significantly smaller than Lazarus, and only his upper body and left leg visibly extended from his brother’s torso. Although his mental capacity will never be fully ascertained, it is believed by historians that Joannes Baptista likely had very limited mental capabilities. It has been recorded that he could neither speak nor appeared to act under his own volition. His eyes were constantly closed and his mouth hung open at all times. The only response Joannes Baptista ever made to human contact was a squirming motion if someone laid a hand on his chest.

Lazarus went on tour with his brother in order to earn a living, even traveling to England to make an appearance at the court of King Charles I in the early 1640s. When not on exhibition, Lazarus would shield his brother from public view by covering him with a cloak. While little documentation exists on the Colloredo brothers, their popularity throughout Europe was neither unique nor unexpected, considering their exceptional physical condition.

The historical traditions of freak shows and exhibitions date back to the reign of England’s Elizabeth I. As early as the 16th century, severe physical deformities and abnormalities were no longer deemed as bad omens or evidence of evil spirits residing within the person. Those with unusual physical characteristics became a public curiosity and were shuttled throughout Europe under the guidance of sideshow managers. While it is unknown whether Lazarus Colloredo employed a performance manager or operated under his own authority when touring Europe, many so-called “freaks” readily agreed to the notion of working under a manager and splitting the profits.

However, it wasn’t until the 19th century that freak shows and novelty acts caught the imagination of a larger viewing public willing to pay for the opportunity to witness human medical oddities. It became a booming business, as people with physical abnormalities grew into a highly profitable market, specifically in England and the United States.

A Brief Description of Sideshows

Sideshows, or freak shows as they are sometimes referred to, contained various forms of entertainment in one evening. Ten in One shows displayed 10 freaks on a platform in front of an audience, as people slowly walked past them. Every now and then, a magician would be thrown into the mix to give the crowd a brief respite from some of the more unsettling abnormalities they were witnessing. However, not all performers were “natural” freaks born with physical deformities. Some were performance artists who had unusual talents, such as fire eating, sword swallowing or full-body tattoos.

Some shows were regarded as inappropriate for women and children and were categorized as “men only” performances. These often included the display of exotic or unnatural objects, such as “pickled punks” which were abnormal fetuses preserved in glass jars. The Piccadilly Egyptian Hall, for example, was home to British naturalist and antiquarian William Bullock’s array of curiosities from around the world, which were on display in the early-19th century.

A Growing Phenomenon

In 1844, American circus pioneer and entertainment business manager P.T. Barnum traveled to England with his latest sensation, Tom Thumb. Born Charles Stratton, Tom Thumb was Barnum’s distant cousin and most recent success story. Barnum trained Stratton in the arts, teaching the young boy how to sing, dance and impersonate famous historical figures. Once Stratton was properly groomed for a life in the public eye, Barnum gave him the stage name of General Tom Thumb.

At just over two feet tall, the diminutive Stratton was instructed to lie about his age, claiming he was 11 years old instead of his actual age of five. Barnum believed that, in making Tom Thumb older than he actually was, it would make his short stature seem all the more remarkable. In order to draw curiosity seekers in London, Barnum also changed Stratton’s nationality from American to English to bring in larger crowds of people hoping to catch a glimpse of a “local” sideshow performer. Tom Thumb was eventually presented to Queen Victoria on two occasions, as she was, herself, a fan of sideshows.

Small American freak shows first started to spring up in 1829, around the time of the arrival of Chang and Eng, the original Siamese twins. As American sideshows began hitting its stride in the 1840s, English versions gained similar popularity. The Victorian era is often viewed as the heyday of the freak show. It was an age of scientific and medical advancements and, consequently, the public was naturally curious about unexplained oddities. Freak shows were staged at both enter- tainment and scientific venues, drawing everyone from young children to seasoned medical professionals.

With the growth of industrialization in large English cities came rapid imperial expansion and the discovery of “exotic” people. Families left the countryside for the city, seeking job opportunities brought about by the countless mills and workhouses that were springing up throughout the nation. Men, women and children were all put to work, making London the greatest and most profitable industrial city in Europe.

As a result of those steady, albeit labor-intensive, hours on the job, people sought new forms of entertainment, to take their minds off their hardships and financial woes. For a small fee, they could enter a world of medical wonders and human oddities, unlike anything they’d ever seen. In an age where scientific reasoning started overshadowing traditional religious values and medicinal advancements claimed stories of miraculous and life-saving surgeries, freak shows introduced the average layman to medicine and science, while enthralling them with tales of exotic locales and mysterious people discovered via colonial expansion.

One famous incident involved Hoo Loo, a Chinese man with a 56-pound tumor on his scrotum. Although he was not publicly displayed as a freak, he was brought to London for a medical procedure. When people got word of Hoo Loo’s arrival, crowds swarmed to the operating theater in Guy’s Hospital to witness the medical wonder. Although Hoo Loo died on the operating table after having bled to death, his story swept through England. Historian Meegan Kennedy argues in her essay, “Poor Hoo Loo: Sentiment, Stoicism and the Grotesque in British Imperial Medicine”, that as a medical oddity, Hoo Loo came to symbolize both the limits of Western medi- cine while also representing the “recovery” or acceptance of the patient (or freak) through empathy from a large audience. He embodied the contrast of both the positive and negative aspects of drawing attention due to a severe deformity. A man like Hoo Loo provoked discussion among those who perhaps knew very little about medicine, science or “exotic” Oriental ideologies in understanding such severe medical anomalies. Although not a sideshow performer, Hoo Loo’s medical predicament was just the sort of “freakery” gaining popularity by the mid-19th century.

The Role of the Showman

The showman was an essential component to the freak show. His talent was in the ability to recruit a person with an unusual disfigurement, disability or talent and use them as an attraction. A showman would often have an alter ego; a stage persona that became a public identity that his audience could recognize. Showmen rarely allowed their freaks to be seen before the show in order to preserve the element of shock and surprise.

The larger-than-life personalities of Victorian-era showmen became an art form in and of itself, as they created narrative histories for each of their freaks in order to create drama and heighten the excitement in the audience. As England’s Tom “The Silver King” Norman later wrote in his memoir, The Penny Showman, “it was not the show, it was the tale that you told”.

The average showman was also often susceptible to the spreading of the occasional lie in order to swindle a little extra cash from the crowd. P.T. Barnum was a shrewd businessman and was not above deception in an attempt to amass large crowds. One of his few faux creations was the Fiji Mermaid, which he debuted in 1842, prior to traveling to England with Tom Thumb. Barnum commissioned a colleague to obtain the skull of a monkey and attach it to the skeletal tail of a large fish.

Tom Norman was the English counterpart to Barnum, picking up where the American showman left off, as Barnum briefly struggled through debts incurred during the 1850s after a handful of poor business ventures. Raconteur-extraordinaire, Norman earned his nickname, “The Silver King” from Barnum himself when the two men met in 1882, after one of Norman’s shows at the Royal Agricultural Hall. Barnum introduced himself and noticed a heavy and expensive-looking silver watch hanging from Norman’s pocket and called him “silver king” and the name stuck.

Like most other showmen, Norman relied on the kindness of strangers in order to house his exhibits. It was common practice for poor tradesmen to rent out their stores for the display of oddities. Norman rented the shops of small businesses for a few days, erecting a small stage or a large curtain inside. In the 1870s, he had debuted Eliza Jenkins, the Human Skeleton, and Balloon-Headed Baby, among others. He traveled with them from Nottingham to Glasgow, renting tiny trade shops along the way. By the early 1880s, around the time of his meeting with Barnum, Norman’s traveling freak show was a surefire hit wherever it went. By the latter half of the 19th century, London’s West End appeared to be a revolving door of exhibitions featuring freaks and novelty acts. It became a permanent fixture at entertainment venues around the city. By 1883, Norman had acquired two of his greatest freak show sensations: Mary Anne Bevan, the World’s Ugliest Woman, and Joseph Merrick, better known as The Elephant Man.

Sideshows were often categorized each night, depending on the entertainment for the evening, whether it was dwarfs, tall men or bearded ladies. It was also com- mon to have specific exhibits set aside solely for women and children. Norman would resort to this tactic on occasion, advertising certain shows as family-friendly and others as geared more towards adults. However, a sideshow exhibit, such as that of the Elephant Man, would have been open to all ages due to his notoriety.

In an attempt to avoid any damage to the reputation of their exhibits, showmen often resisted having doctors visit their performers for fear that a diagnosis of the freak’s ailment or a classification of their deformity would ruin the appeal of the show. Their conditions would appear less mysterious or exotic if given a medical definition and the public would lose interest. Contrary to popular belief, freaks were rarely mistreated by the showmen who controlled their schedules. When Dr. Frederick Treves attacked Norman in his 1923 memoir, The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, Norman retaliated. Even though, by that time, it had been years since the death of Joseph Merrick, Norman had no intention of allowing Treves to portray him as the villain in the short life of the Elephant Man. Treves had accused Norman of abusing and mistreating Merrick, forcing him to display his body against his own free will. In February 1923, Norman published a response in the World’s Fair and stated that, “the big majority of showmen are in the habit of treating their novelties as human beings, and in a large number of cases as one of their own, and not like beasts”. Barnum likely would have approved of Norman’s published rebuttal, having built a strong rapport with the majority of his freaks in the US, specifically with regards to his enduring friend- ship with Tom Thumb.

The Freaks!

“Perhaps she would get me, after all!/If the links should break, I might feel small,/Young as I was, and strong and tall,/And blest with a human shape,/To see myself foil’d in that lonely place/By a desperate brute with a monstrous face,/And hugg’d to death in the foul embrace/Of a loathly angry ape”. ~Arthur Munby’s “Pastrana”~

When discussing freaks shows in England, it is impossible not to mention its connection with British ideology and imperial imagery. The narrator of Arthur Munby’s poem, Pastrana, feels his masculinity is under threat after he first lays eyes on Julia Pastrana, one of the Victorian eras most well-known freaks. He feels small in comparison to a human being who more resembles an ape than she does a woman. It illustrates the argument historians make about the role of the freak in 19th-century England. In a time of social upheaval and global expansion, such an extraordinarily abnormal figure as Pastrana would have helped drive home to the public what it meant to be British, as opposed to an exotic, foreign “other”. The shows came to represent a national identity, reinforcing the notion of what makes one quintessentially British and what does not. Julia Pastrana was a Mexican-born woman suffering from hypertrichosis, a disease that results in the person being covered from head to toe in long, thick hair. Other indicators often included exaggerated facial features, including a large nose and thick lips. She toured Europe in the 1840s and 1850s under the guidance of Theodor Lent, the man who would eventually become her husband. However, Pastrana died shortly after giving birth to a stillborn baby who had similar features to her own. Therefore, instead of abandoning the tour, Lent had his wife and child mummified. Even in death, Pas- trana was destined for a life in the eye of the public.

Despite the sad circumstances surrounding Pastrana’s life, there were many freaks that were able to separate their stage persona from their own identity and gen- uinely enjoyed their newfound fame. Far from considering themselves exploited, these freaks became self-consciously complex in their stage presentations. Tom Thumb, Barnum’s tiny sensation, is an example of one who made his stage persona a caricature, completely separate from his identity as Charles Stratton, a man who eventually got married and had children of his own. Like an actor, Stratton was able to shed his guise as Tom Thumb at the end of each day.

Krao Farini, a Burmese girl who had been performing since the age of six, worked for Barnum from the 1880s until her death in 1926. She was billed as “The Missing Link”, a play on Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, thus integrating science and Darwinism with entertainment. Farini had simian-like qualities, including flexible limbs and a hairy body. Despite her youth, she often performed scantily clad and audience members were allowed to reach out and touch her at the end of each show. This outrageous performance contrasted with her much more reserved personality, thus separating her personal identity from that of her shocking role as the Missing Link in entertainment venues.

Freaks were often perceived as apprehensive, docile and unhappy with their lot in life. In many cases during the Victorian era, nothing could be further from the truth. Many defended themselves against their managers, talking back and demanding raises. As early as 1851, it had become popular to sell trading cards of popular freaks throughout England and the US. Profits from these images went straight into the pockets of the performers themselves, as opposed to the showmen. Isaac W. Sprague, the American Human Skeleton, had one of the most successful trading cards. At 5’6”, Sprague weighed only 43 pounds. As he toured with Barnum in the 1860s, he made a good sum of money off of the sale returns from the card. Some of the more willing performers, like Sprague, even penned their own biographies to be published in freak show pamphlets.

Although showmen and freaks would often split the profits from ticket sales and money made off of pamphlets or cards, the client was better off in the end. While the showmen had to pay for store rentals, heating and lighting, profits given to the sideshow performers went straight into their hands. It was not uncommon for freaks to be better off, in terms of wealth, than the majority of the public who came to see them perform.

It was no small wonder that both showmen and performers, alike, argued that it was better if the freaks were in public, displaying their abnormalities for profit, rather than struggling to live among everyday people without a job and in complete isolation.

The Decline of the Freak Show

By the 1890s, the popularity of freak shows started to dwindle. A variety of factors played a pivotal role in its almost complete disappearance by the 1950s.

British social historian and journalist, Henry Mayhew, had always been opposed to the very existence of both the popular sideshows and “penny gaffs” (considered a bawdy type of entertainment). As early as 1861, in his study, London Labour and the London Poor, Mayhew wrote vehemently against them. He rejected the notion of such shows as a valuable form of entertainment, dismissing them as nothing more than moral corruption and human degradation. He wrote that, “instead of being a means for illustrating a moral precept, it turned into a platform to teach the cruelest debauchery”. In Mayhew’s opinion, the “men who preside over these infamous places know too well the failings of their audience”.

Although Mayhew voiced his aversion towards “low forms” of entertainment in the 1860s, it wasn’t for another 30 years before the rest of the public started to adapt to his way of thinking. In the early years of the 20th century, a rise in disability rights inspired people to turn against sideshows and what they deemed as exploitation parading as entertainment. With railways, steamships and more access for people to travel, the idea of the foreign and exotic “other” started to lose its appeal as people left England or the US to explore the world for themselves.

With advances in medicine, freaks were faced with actual diagnoses. As a result, sideshows began losing their appeal as their physical or medical conditions were no longer thought of as miraculous or entirely unique. Some even stayed away from sideshows for fear of catching the freaks’ “diseases”.

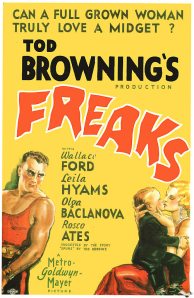

The First World War glorified its returning heroes, while sideshow performers were ignored as they stayed at home, performing for reduced price rates, while men and women fought on the front. By the 1930s, sideshows were deemed as lack- ing in dignity and the value of novelty acts was wearing thin. Tod Browning’s 1932 American film, Freaks, was universally reviled upon release. Featuring real-life freaks, such as the limbless Prince Randian, the legless Johnny Eck and conjoined twins Violet and Daisy Hilton, the plot revolved around a woman who marries a midget sideshow performer named, Hans (played by Harry Earles). Due to the controversy surrounding the film, many scenes were heavily edited and, as a result, have been lost over time. However, Freaks is now considered a cult classic and is still screened around North America at cult film festivals.

Many nations took to banning sideshows, including Germany in 1937. With the rise of television, the entertainment provided by freak shows was all but lost. More and more people shunned this “low brow” form of entertainment in favor of staying at home and watching television in the comfort of their own home.

Unable to land proper jobs and unwilling to fade quietly into the background without any money, freaks took to performing in traveling carnivals and museums for small amounts of cash.

Coney Island in New York remains one of the few providers of sideshow entertainment left in the world. Although well past its heyday during the early-20th cen- tury, Coney Island remains a staple of the type of old-fashioned freak shows that were once so popular. Since 1983, “Sideshows by the Seashore” has been a popu- lar tourist attraction. It also boasts the last true Ten in One freak show in the world.

Despite their diminished popularity, the history of freak shows continue to ingite our curiosity.

Photo Captions

Image One: A 17th century sketch of the Colloredo brothers, Lazarus and Joannes Baptista.

Image Two: Charles Stratton traveled to England with P.T. Barnum in 1844 under the stage name, General Tom Thumb.

Image Three: Julia Pastrana toured Europe as either the Ape Woman or the Bearded Lady.

Image Four: The poster for the 1932 film, Freaks.

Sources:

Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Thompson, Rosemarie. Freakery: Cultural Spectacle of the Extraordinary Body. NYU Press, 1991.

Great article, Laura.

Although it seems that for some of the “freaks” their lives as curious attractions brought them a better living standard than the one they would have had if they had just lived “normally”, I find those shows unpleasing. I find the idea of getting entertainment by looking at disfigured people and probably making fun of them or secretly thanking God for not being like them repulsive. But you’re definitely right, it’s still fascinating to wonder how and why they worked and became as famous as they did.

I assumed that as well, when I first started doing research. I figured they were all mistreated and hated being paraded in front of people. It was eye-opening to realize a lot of them embraced it. It was a way for them to make money. Many became their own managers.